Weingart: ‘what still surprises and inspires me today: to turn blank paper into a printed page.’ Nothing can be more reassuring than to read words like these from someone who has almost forty years of experience behind him. What more can you ask for in a career?

Weingart was born in the midst of the World War II in Germany. Most famous for his experimental, expressive work that broke the mould of classical Swiss typography, Weingart began his typographic career in the early sixties as an apprentice of hand composition at a typesetting firm. He then decided to further his studies at the Basel School of Design in Switzerland, the cradle of classical Swiss typography. Following his rather unsuccessful attempt at completing his course, Armin Hoffmann, who was then the head of the Basel School, invited him to teach there, by the sheer admiration of his work. He has been teaching there ever since and had made extraordinary impact on the contemporary typographic landscape.

Swiss typography was founded upon the teachings of the Bauhaus in Germany soon after World War II and became a rational approach to typography. The use of grid systems was the key to the logical disposition of type and images on the page, along with sanserif typefaces for clear, functional communication. It was believed that typography should be unobtrusive and transparent, in order to clearly communicate its textual content. By the beginning of the sixties, the language of Swiss typography had already gained reputation the world over. Swiss typography became synonymous with corporate design for multinationals, and subsequently referred to as the ‘international typographic style’.

and then came.....Wolfgang Weingart- it can be said that he started it all, he ignited the spark of ‘typographic anarchy’ that exploded on the verge of the nineteen nineties, he began what was subsequently dubbed ‘Swiss Punk’, ‘New Wave’ ,perhaps even post-modernism.

‘not only one conception of typography exists in Switzerland.’ His experimental typography was also Swiss, because it was a ‘natural progression’ from the classical Swiss typography as we know it. His typographic experiments were strongly grounded, and were based on an intimate understanding of the semantic, syntactic and pragmatic functions of typography. Whereas ‘traditional’ Swiss typography mainly focused on the syntactic function, Weingart was interested in how far the graphic qualities of typography can be pushed and still retain its meaning. This is when the semantic function of typography comes in: Weingart believes that certain graphic modifications of type can in fact intensify meaning. ‘What’s the use of being legible, when nothing inspires you to take notice of it?’

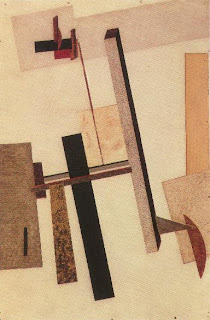

Weingart’s work is characterized by his painterly application of graphical and typographical elements. The emotionally-charged lines, the potent, image-like qualities of his type, the almost cinematic impact of his layouts, all speak of his great passion of creating with graphical forms. His typographic layouts are compelling yet lucid, free yet controlled. Some of his personal work is almost akin to landscape paintings, only that his paintbrush is replaced by type, rules and screens. He does not create a divide between fine art and typography. His inspirations were mainly drawn from the processes of typesetting and reproduction, where he finds great pleasure in discovering their characteristics and pushing them to their limits.

Weingart works with a very limited palette of typefaces. He suggests that four typefaces are enough to address all typographic problems. One of these typefaces would certainly be Akzidenz Grotesk, an early sanserif of the grotesque genre designed by the Berthold Foundry in Germany at the close of the 19th century. ‘I grew up with Akzidenz Grotesk and I love it. Akzidenz Grotesk has a certain ugliness to it, that’s why it has character.’ The simplicity of his choice of typefaces speaks of his fondness of simple tools.

‘For me, typography is a triangular relationship between design idea, typographic elements, and printing technique,’ writes Weingart. The possibilities that these technologies offer seem endless to him, and he finds it hugely satisfying to explore the materials: ‘The thing that is so special for me… is the variability of the materials under the influence of idea and technique.’

It is the tension between his desire to express and his consideration for communication that creates this interesting mix of work and his perpetually inquisitive working ethos.‘That’s my schizophrenic personality’.

Weingart’s typographic experimentations spanned across three different eras of typesetting technology: letterpress, phototypesetting and the computer. Yet, despite how readily he accepted and pushed the boundaries of the letterpress and phototypesetting processes, he is rather unenthusiastic about the computer technology. The computer, to him, is too illusive. He compares the computer to a digital watch: a traditional watch shows a ‘landscape’, it tells a story; a digital watch only shows a particular moment. Graphic design is in a big crisis. The education in our school is not the best any more. The value of living has changed. The computer and electronic tools in general are destroying our natural needs.’ The natural needs, perhaps, is our need to create, to express.